What is interesting to me about this particular clip is that it uses narrative to write a metaphor of broader perspective on top of documentary footage. The workers are referred to as "figures," casting them as orchestrators of a cultural and possibly archetypal narrative. When Herzog says "Has life without fire become unbearable for them?" he does not speak only of the men igniting the oil geyser, but of a madness within humanity that craves the spectacular chaos that is unfolding in front of the camera. As the men watch the fire, they smoke cigarettes, pointing to the power, control and fearlessness that humanity has been able to manifest over a potentially deadly natural phenomena. The smoke from the fires is black, thick and destructive, like a cigarette is to the body, implying an impending demise. There is a sense of truth and also of fiction that ebbs and flows throughout Herzong's work.

The spectacle of metaphysical arrest that this scene instills in me seems to correspond with the concept of the sublime. In his essay Comprehending Appearances: Werner Herzog's Ironic Sublime, Alan Singer argues that to read Herzog's work as sublime is an oversimplification of his formal process. Singer unravels (in extremely tangled language) the production of a second-order reality in Herzog's films through his use of time, narration, apparatus (the camera) and style. These formal devices create cultural meaning and a point of view that ultimately result in a critical perspective of human temporality rather than a spiritual or subjective expression of sublimity. In other words, the films produce within a viewer a self-conscious awareness of history, irony and narration that give a sense of perspective and consequence that the would be denied if the film simply took the sublime as its motivation.

The scene below is also from Lessons In Darkness.

The aerial movement and disorienting smoke are what Singer refers to as the touchstones of Herzogs work: images that must be seen though detours of perception. As William L. Fox states in his book Terra Antarctica: Looking into the Emptiest Continent "sight is our only long distance sensing mechanism, and in a space of such vastness (speaking of the Antarctic) we rely primarily on it for orientation and a sense of self relationship to what is around us." The cinematic effects in the above clip do give the film a sense of disorientation but the arid, smoke filled desserts of Kuwait must have a similar disorientation even before Herzog filters them though his lens. The charred and burning land that is the setting of Lessons In Darkness is then already biologically disorienting and perhaps our perception of this place is actually organized as much as it is disoriented though the act of filming.

A study by the artists Vitaly Komar and Alex Melamid, and cited in Fox's book, surveyed people around the globe and found that, of all the styles and subjects of painting, we most prefer traditional landscapes of wooded areas with visible water. He presumes that this cross cultural desire indicates a biological longing for a deep ancestral home where our evolution occurred. In the antarctic, Fox speaks of disorientation and a collapse of visual perception that is the result of our eyes inability to respond to a lack of contrast, color and scale because we developed in more lush environments that have these characteristics. This same collapse of perception must exist on the ground for the men in Lessons In Darkness and is, I believe, palpable when viewing the film. This is the tension within the film; a feeling of disorientation, of what Corrigan calls the departicularization or reparticularization of the sublime, and a progressive narrative that is woven into history and documentary.

These articles reminded me of some of the issues in An-My Le and Richard Mizarch's work.

An-My Le - Night Operations #7, 2003-04

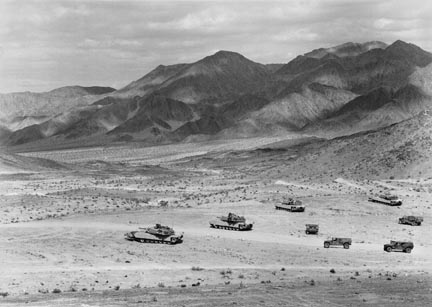

An-My Le - Mechanized Assault, 2003-04

When creating the series 29 Palms, An-My Le documented a military training camp in California's Mojave Desert that was used as a preparation site for soldiers before they were deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan. Using formal process and narrative in a way similar to Herzog, her images depict a real event but comment on broader cultural concerns. I am immediately compelled to compare Le's images to the photo journalistic representations of war that I have seen in the newspaper. This is in part because she uses a chalky black and white pallet that abstracts the locations in her photographs from a specific place to a general description of war landscape. The pallet also refers to the texture and contrast typically seen in newsprint media. Unlike newspaper photographers who often follow Robert Capa's age old advice "If your pictures aren't good enough, you weren't close enough," An-My Le's photographs are distanced and removed. This vantage point reminds me that my ideas about war are not from a first hand encounter but are instead distanced and mediated and that a sequence of events about the way war ought to play out is also mediated for soldiers through preconceptions and training long before they are lay foot in a war territory.

Particularly in the Night Operations image I posted, I get a sense of the sublime as it relates to what we often call shock and awe. Awe, or the feeling of the sublime is tempered by the knowledge that destruction and death are being caused by this event.

Richard Misrach - Swimmers, Pyramid Lake Indiana Reservation, Nevada, 1987-93

Richard Misrach - Desert Fire, #135, 1984-1993

The significance of social documentary in Richard Misrach's Desert Cantos photographs as well as the formal beauty and often fiery pallet remind me of Herzog and Lessons In Darkness.

It's interesting that we both thought of Misrach and Herzog as connected, though through very different films and very different images.

ReplyDeleteGreat clips, Allison. And as always, great insights. The scenes you chose from Lessons of Darkness remind me of how Fox was talking about how disorienting being Antarctica can be. There are moments where you can't tell which end is up. Instead of the 'white out' of the snow, you experience a 'black out' of the smoke. I've never thought about how much I take the horizon for granted until reading about the test pilots and watching your Herzog clips of the oil well smoke.

ReplyDelete