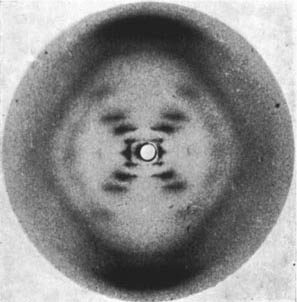

1952 x-ray photograph by Rosalind Franklin that eventually led to the conclusion that DNA has a double helix shape.

But the biological gaze does not end with looking. To discover or reveal the origins of life we must reach into the pristine unknown and untouched as Franklin, Watson and Crick did. Few untouched realms remain and those that do are locked beyond our scientific capacity (distant space, string theory). To reach new discoveries and further our scientific understandings of the universe we must move, collide and destroy. The gaze, from a biological standpoint, has "become increasingly and seemingly inevitably enmeshed in actual touching."

The Tevatron Particle Accelerator at Fermi Lab near Chicago can collide sub-atomic particles to create substances that were abundant in the early universe. (and it is totally outdated)

Though Franklin was hardly naive to the transgressions of her work, there are compelling questions raised in this reading about the ways technology and photography separate vision from interaction and facilitate constructed understandings of the origins of life. Many technological devices aid us in investigating places where our senses cannot go unaided, like a microscope. Are those places our experiments shouldn't go? How well can we understand molecules, places, cultures and our own nature through the creation and transmission of information via electronic media? Are there technological networks with functions that mirror biology - as in the world wide web and the web of life? To begin to answer these questions, I will turn to our second reading, Art Is Nature: An Artist's Perspective on a new Paradigm by George Gessert from the March/April issue of Art Papers. (link to source)

Gessert begins by outlining two approaches to nature: a Darwinian view and an ecological view. Here is a chart of the overlaps and distinctions between these two viewpoints.

click to enlarge

I don't think of these two viewpoints as poles, I think of them as perspectives. From a Darwinian perspective, technology, photography and both "webs" are a part of our nature. They help us understand ourselves better because they are a part of the output of our existence. There are no ethical or ecological boundaries to our exploration, but this perspective is non-dualistic so it allows for the continuation of nature without us. In other words, the Darwinian perspective is not interested in retaining a certain amount of biodiversity or in the continued existence of a particular species. Nature is simply an ever shifting set of physical systems that favor the lifeforms they can support.

The ecological perspective, the human centric of the two, is more interesting in the context of the questions outlined above. Biodiversity and the protection of ecological relationships are cornerstones of this viewpoint. It also leaves open the possibility of humans discontinuing some or all of their interactions with natural systems in favor of technology. As human behaviors and desires are translated into technology, could they eclipse ecology? I do not mean that ecology could cease to exist. As we translate more and more of our being into imagery, machinery and virtual space, we could come to understand the world technologically first. Technology could some day mask biology In some ways it already does. When I was fed intravenously at the hospital, technology was altering my biological behavior and masking any need I had to eat.

There are two ways to think of technology, an apparatus (as in a computer) and a system (as in a computer network). For the last few days I have been trying to figure out a way that either of these things could create ecological relationships on their own. I have concluded that they can't. Of course they effect ecological relationships under our direction, but they have no will or biological existence. They are no more biological than the mail, a system comprised of apparatuses (pen, paper, envelopes) and a network that transmits ideas/goods (USPS). But the mail system is firmly planted in our physical, dimensional realm. Maybe technology is of another realm, the virtual realm.

This other realm is not the physical hardware and devices of technology, but rather the network which is in every appliance and computer and is also expanded to connect our mobile phones and the internet. EVERYTHING that travels through this network is mediated. Objects, ideas, images and texts pass out of the biological realm when they enter the virtual realm. As the world is mediated, it is also refracted and made oblique.

This is also true of the photograph. Franklin's process of imaging DNA was, at the time, the only way she could reach any conclusions about the genetic instructions that shape our physicality. The biological gaze may only inform us obliquely, but it does offer some understanding. Of course humans do, and I argue must, try to make sense of something so fundamentally curious. The drive to understand the world around us is in our nature. Communication, questioning, analysis and skepticism are biological characteristics that have helped humanity survive and flourish.

Art is one of the most important venues for this discussion. It often asks a question that I posed a few paragraphs back. If we have the tools to investigate, should we?

Many of the artists Gessert brought up in his article pose this question. Gary Schneider asks what exactly a body looks like. With Genesis, Eduardo Kac seems to question the possibility of ever demythologizing our true origin. Most interesting to me was the piece trophoblast by David Kremers.

trophoblast by David Kremers (1992) is made from genetically altered E. Coli bacteria trapped in synthetic resin. The E. Coli is alive inside of the piece, but its growth has been halted through the resin sealing process.

Gessert sees this work as a representation of an ambiguous embryonic life form. Because it could be animal or human, we are connected to other species through its appearance. It is also alive, demanding custodianship and redefining the boundaries of what an art object can be made of. Those are compelling observations, but Gessert's assessment

This is not the only piece Gessert assesses with an awkwardly slanted interpretation. Over and over, he argues that certain works move beyond "narrow human concerns" by ignoring any potential content that does not serve his point. Maybe Gessert's definition of narrow is narrower than mine, but I see each piece questioning the ethical and scientific boundaries of human intervention and control with a hearty dose of multiple human concerns. And why not? Isn't ecology a human concern after all?

Other Artists:

Frtiz Haeg

Paul Thek

Phoebe Washburn

It's interested to think about Fritz Haeg's work in terms of the human-centeredness question. With the exception of the eagle nest, almost all of the animal "estates" that he built were not meant to resemble the homes these animals might build for themselves. They were the kind of homes that we see that people make for animals and put in backyards or nature preserves. I wonder why he chose not to replicate the hollowed trees and underground tunnels that these creatures would have actually lived in?

ReplyDelete